Postgres Types

Introduction

This is a written summary of the content of my talk Postgres Types, given at PostgresConf 2024.

I discuss foot-guns with built-in types (most folks don’t know what timestamptz really is!), range types (built-in and custom) and composite types.

Most folks will learn something from this material.

Built-in types

I am grateful to [a number of the Saints of the postgresql_general list for help getting this section right. In particular:

- Laurenz Albe

- Ian

- Adrian Klaver

- David G Johnston

- Tom Lane

- Paul Jungwirth

Timestamp With Timezone (timestamptz)

Most Postgres users believe timestamptz stores a timestamp and a time zone. It’s certainly understandable given the type’s name. This belief is wrong.

Let’s say I have this timezone:

SHOW timezone;

TimeZone

---------------------

America/Los_Angeles

I create a table:

# CREATE TABLE tz_test(

x TIMESTAMP WITH TIMEZONE

);

CREATE TABLE

Now I insert some data and retrieve it:

# INSERT INTO tz_test(x)

VALUES

('2024-04-17 09:00:00 -07');

# SELECT x FROM tz_test;

x

------------------------

2024-04-17 09:00:00-07

Let’s see what the Postgres Docs say (emphasis mine):

For timestamp with time zone, the internally stored value is always in UTC (Universal Coordinated Time, traditionally known as Greenwich Mean Time, GMT). An input value that has an explicit time zone specified is converted to UTC using the appropriate offset for that time zone. If no time zone is stated in the input string, then it is assumed to be in the time zone indicated by the system's TimeZone parameter, and is converted to UTC using the offset for the timezone zone.

We can see this if we insert a value with a non-system timezone:

INSERT INTO tz_test(x) VALUES (

'2024-04-17 09:00:00 +00');

# SELECT x FROM tz_test;

x

------------------------

2024-04-17 09:00:00-07

2024-04-17 02:00:00-07

Notice the conversion that happened to the second value.

Timestamp

There is an issue with plain timestamps, too.

# CREATE TABLE timestamp_test(

x TIMESTAMP

);

CREATE TABLE

Now we insert a value:

# INSERT INTO timestamp_test(x) VALUES('2024-04-18 12:00:00+07');

# SELECT x FROM timestamp_test;

x

---------------------

2024-04-18 12:00:00

Note that the timezone provided in the value is ignored!. This is because Postgres parses the value as just a timestamp. The simple solution is to cast the value to TIMESTAMPTZ:

# INSERT INTO timestamp_test(x)

VALUES(

'2024-04-18 12:00:00+07'

::TIMESTAMPTZ

);

Time With Timezone (TIMETZ)

You might imagine now that you know what TIMETZ is, but in fact TIMETZ does include a timezone value. Note, however that the timezone is treated as just an offset from UTC, and does not eg take account of daylight savings.

Money

The Postgres Docs say (emphasis mine):

The money type stores a currency amount with a fixed fractional precision… The fractional precision is determined by the database's lc_monetary setting.

So you can run into trouble like this:

# SET lc_monetary='en_US.utf8';

SET

# CREATE TABLE t (m MONEY);

# INSERT INTO t VALUES('$1000.00');

INSERT 0 1

# TABLE t;

m

-----------

$1,000.00

(1 row)

What happens if we change lc_monetary?

# SET lc_monetary='ja_JP.utf8';

SET

# TABLE t;

m

-----------

¥100,000

CHARACTER(…)

You’ve probably encountered the advice to just always use TEXT for strings in Postgres. But you maybe don’t know just how bad and stupid the CHARACTER(…) types really are. I mean, this is fine:

# SELECT 'a'::character(10);

bpchar

════════════

a

It’s a 10-character string, right?

Wrong.

SELECT

LENGTH('a'::character(10));

length

════════

1

WAT?

It gets worse:

# SELECT 'a'::CHARACTER(10) || 'b'::CHARACTER(10);

?column?

══════════

ab

The documentation makes it clear (emphasis mine):

Values of type character are physically padded with spaces to the specified width n, and are stored and displayed that way. However, trailing spaces are treated as semantically insignificant and disregarded when comparing two values of type character.

There’s more (emphasis mine):

Trailing spaces are removed when converting a character value to one of the other string types. Note that trailing spaces are semantically significant in character varying and text values, and when using pattern matching

Don’t blame the Postgres developers; all of this nonsense is required by the SQL standard (no link because you have to pay for a copy).

ENUMs

This seems worth mentioning. The advantages of Postgres ENUM types are:

- Performance; and

- Simpler SQL

I’ll take almost anything that simplifies the general godawfulness of SQL. Still, there are some significant disadvantages:

- Performance

- “An enum value occupies four bytes on disk.”

- Changes involve DDL

- Fixed order

- Fixed case

- Non-localisation friendly

- Less Portable

Performance is both an advantage and a disadvantage because 4 bytes is usually significantly shorter than storing a string. But even an ENUM with only handful of values occupies 4 bytes on disk. However, a foreign key reference to a lookup table with a SMALLINT key would only require two bytes.

RANGE types

Thanks to Paul Jungwirth for help with this section.

A quick refresher: a range in Postgres is described by giving its lower and upper bounds, with the bounds indicated by square bracket (inclusive) and parenthesis (exclusive):

SELECT '[3,7)'::int4range;

int4range

-----------

[3,7)

(1 row)

/* contains 3, 4, 5, 6 */

There is another way to write the same thing:

SELECT int4range(3,7, '[)');

int4range

-----------

[3,7)

(1 row)

Note how the bounds types are indicated in the third argument.

Postgres 14 introduced multiranges:

SELECT

'{[3,7), [8,9)}'::int4multirange;

/* contains 3, 4, 5, 6, 8 */

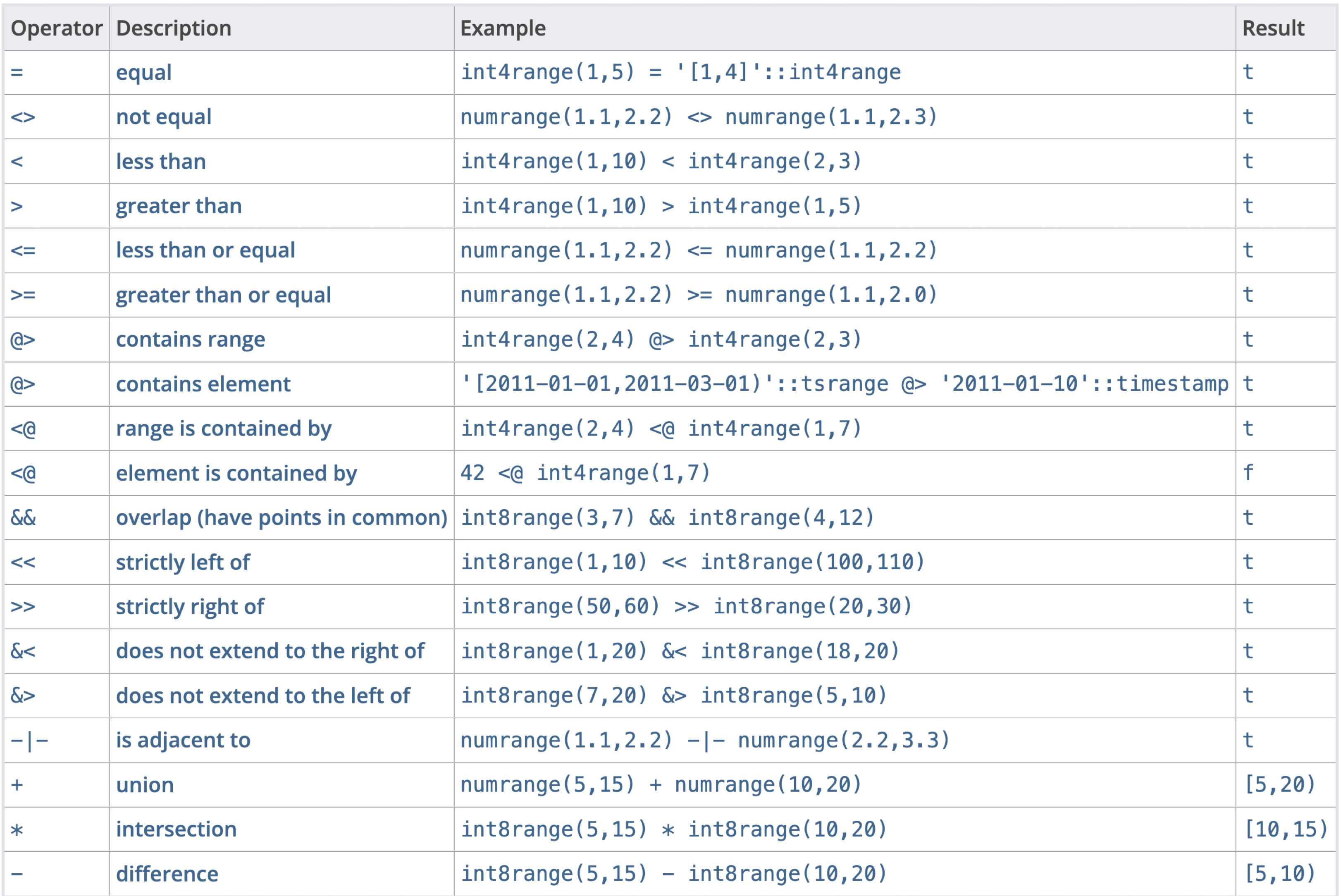

Postgres has a really complete set of operations on ranges.

It is useful to create custom range types, which is done like this:

CREATE TYPE

inetrange

AS

RANGE (subtype = inet);

You can create range values like this:

SELECT '[1.2.3.4,1.2.3.8]'::inetrange;

inetrange

-------------------

[1.2.3.4,1.2.3.8]

You can also do this:

SELECT

inetrange('1.2.3.4', '1.2.3.8', '[]');

inetrange

-------------------

[1.2.3.4,1.2.3.8]

Having done this, you can use all the lovely range operators freely:

SELECT

'1.2.3.6'::inet

<@

'[1.2.3.4,1.2.3.8]'::inetrange;

?column?

----------

t

(1 row)

A great use for ranges is exclusion constraints. This constraint ensures that the range values don’t overlap between rows.

CREATE TABLE

geoips (

ips inetrange NOT NULL,

country_code TEXT NOT NULL,

latitude REAL NOT NULL,

longitude REAL NOT NULL,

CONSTRAINT geoips_dont_overlap

EXCLUDE USING gist (ips WITH &&)

DEFERRABLE INITIALLY IMMEDIATE);

Note that this creates a gist index on the ips field. However, just what we’ve done so far will be quite slow. We need to provide some more information for the index to be efficient. We need to provide a distance function as part of our type for gist to work properly.

CREATE OR REPLACE FUNCTION

inet_diff(x inet, y inet)

RETURNS

DOUBLE PRECISION

AS$$BEGIN

RETURN x - y;

END;$$LANGUAGE 'plpgsql'

STRICT IMMUTABLE;

Now, we can provide this function as part of the type definition:

CREATE TYPE

inetrange

AS

RANGE (

subtype = inet,

subtype_diff = inet_diff

);

Unfortunately, there is still a problem.

SELECT

'[1.1.1.1,1.1.1.3)'::inetrange = '(1.1.1.2,1.1.1.2]'::inetrange;

?column?

----------

f

(1 row)

These two ranges are actually equivalent. Postgres supports another argument to the CREATE TYPE function called CANONICAL, which takes a value and returns a standard representation of it.

Unfortunately, at the moment, it is only possible to create a CANONICAL function in C, which is beyond the scope of this piece.

COMPOSITE types

From the Postgres docs:

A composite type represents the structure of a row or record; it is essentially just a list of field names and their data types.

In just any modern programming language, you can define a data type that consists of a map from a fixed set of field names to a fixed set of types:

//Java

class inventory_item {

String name;

int supplier_id;

float price;

}

You can do precisely the same thing in Postgres:

# CREATE TYPE inventory_item AS (

name text,

supplier_id integer,

price numeric

);

The syntax of this is symmetric with CREATE TABLE, although unfortunately you can’t declare constraints.

Note the AS keyword. Without this, you are declaring a type a different way, which requires writing C code, which is out of scope for this piece.

Composite types are fully first-class citizens in a Postgres database. You can, for example, declare a column in a table to be of a composite type:

CREATE TABLE on_hand

item inventory_item,

count integer

);

You can construct such a value by writing a ROW value, which is just a tuple inside parentheses:

INSERT INTO

on_hand

VALUES(

( 'fuzzy dice', 42, 1.99),

1000

);

You access the fields inside a composite type much as you do in most languages:

SELECT

(item).name

FROM

on_hand

WHERE

item.price > 9.99;

Note the parentheses around item in the first instance. This is required because ~SQL is terrible~ Postgres would normally regard “item” as the name of a table.

This is how you include a table or alias name if that is required:

SELECT

(on_hand.item).name

FROM

on_hand

WHERE

(on_hand.item).price > 9.99;

SQL ugliness aside, it really all just works as you would expect:

UPDATE

on_hand

SET

item.price = (item).price * 1.1;

Nesting type definitions works just fine. So, define an address type:

CREATE TYPE

address

AS (

street text,

city text,

zip int,

state text

);

Now, define a person type with a address field:

CREATE TYPE

person

AS (

addr address,

given text,

family text

);

We can have a person-valued field:

CREATE TABLE

folks(

them person,

notes text

);

You write nested types using nested row values:

INSERT INTO

folks(

them,

notes

)

VALUES(

(

('1 Main St', 'Herotown', 90210, 'CA'),

'Andreas',

'Freund'

),

'The hero of the hour'

);

Another example of composite values being first-class citizens is that you can use them in functions:

CREATE FUNCTION

pp(

addr address

)

RETURNS

text

LANGUAGE plpgsql

PARALLEL SAFE LEAKPROOF COST 1

AS $function$BEGIN

RETURN

addr.street || E'\n' || addr.city || E'\n' || addr.state || E'\n' || addr.zip;

END;$function$

You can use this as expected:

# SELECT

pp(

(them).addr

)

FROM

folks;

pp

-----------

1 Main St+

Herotown +

CA +

90210

(1 row)

This reminds me of a really nice feature that deserves to be more widely known. Any function that takes a single argument like this can be written in a more OOP style, like a method. This is exactly equivalent to the preceding query:

# SELECT

(them).addr.pp

FROM

folks;

pp

-----------

1 Main St+

Herotown +

CA +

90210

(1 row)

Note that we’re now writing .pp rather than pp(…)

Perhaps now you can see why Postgres hasn’t been in any hurry to add computed columns. Postgres has had an equivalent feature for decades!

There is a nice, if useless symmetry in this feature in Postgres. We’re all familiar with referring to a field value like this:

# SELECT

folks.notes

FROM

folks;

notes

----------------------

The hero of the hour

(1 row)

Interestingly, you can also write the same thing as:

# SELECT

notes(folks)

FROM

folks;

notes

----------------------

The hero of the hour

(1 row)

I’m a fan of the function application notation as a way to provide a computed field, but although I love orthogonality, I’m not sure of a good use for this notation. It’s just confusing. Perhaps with code generation?

Here is another way to define a composite type:

# CREATE TABLE

inventory_item

AS (

name text,

supplier_id integer,

price numeric

);

Whenever you define a table, you define a type with the same name. The type represents the value of a row of the table.

It is possible to work in the opposite direction, too. Having defined a type, we can define a table of that type, and also define constraints while we’re at it:

# CREATE TABLE

inventory_items

OF

inventory_item(

name NOT NULL,

price NOT NULL

);

Postgres lets us write multiple functions with the same name, as long as they can be differentiated by the arguments they take. Here, we define another pp function for our folks rows:

CREATE FUNCTION

pp(

f folks

)

RETURNS

text

LANGUAGE sql

PARALLEL SAFE LEAKPROOF COST 1

RETURN

(f.them).given || ' ' || (f.them).family || E'\n' || (f.them).addr.pp;

Note that we call the original version of the pp function.

In any query, you can refer to the whole row with the name of the table:

# SELECT

folks.pp

FROM

folks;

pp

-----------

1 Main St+

Herotown +

CA +

90210

(1 row)

This ability, to write a function of a row, is a greatly under-used feature of Postgresql that can really clean up SQL code.

What we have discussed so far now lets us adopt a deeper understanding of the * operator: it expands a composite type into all its constituent columns. So we can do this, which returns the composite type value:

# select them from folks;

them

------------------------------------------------------

("(""1 Main St"",Herotown,90210,CA)",Andreas,Freund)

(1 row)

But if we apply the * operator:

# select (them).* from folks;

addr | given | family

---------------------------------+---------+--------

("1 Main St",Herotown,90210,CA) | Andreas | Freund

(1 row)

Issues

Whenever I discuss these ideas, I encounter a common objection, which is wrong.

But this isn’t relational

It just is. In fact, it’s relational from two different perspectives.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia In database theory, a relation, as originally defined by E. F. Codd,[1] is a set of tuples (d1,d2,...,dn), where each element dj is a member of Dj, a data domain.

The relational model is silent about what types of values the database can store.

In fact, the original theory contemplated client applications defining and storing custom types.

Postgres, Oracle, and surprisingly, SQLite are the only databases I know of that can store arbitrary types like this (the way this is done in SQLite is a bit of a trick; stay tuned to see how it is done).

Storage efficiency

I’d like to thank Steven Frost for his help with this issue.

Composite Types, from a language perspective, works just about as perfectly as it can in SQL. Semantically, we could use them just as we use the same feature in our other programming languages, to achieve the same ends, to simplify our code in the same way.

Except. Except the matter of storage.

We define a simple composite type:

CREATE TYPE

twoint

AS (

a int,

b int

);

We create two tables, one containing a field of the composite type, another two equivalent separate fields:

CREATE TABLE

t1 (

a int,

b int

);

CREATE TABLE

t2 (

c1 twoint

);

We insert equivalent data into each table:

INSERT INTO

t1

VALUES

(1,2);

INSERT INTO

t2

VALUES

((1,2));

How much space do these values occupy? For the regular table:

# SELECT

pg_column_size(t1.*)

FROM

t1;

pg_column_size

----------------

32

(1 row)

And for the composite value:

# SELECT

pg_column_size(t2.*)

FROM

t2;

pg_column_size

----------------

53

(1 row)

The composite value is 21 bytes bigger! That’s actually pretty significant, if you’re storing a lot of these values.

The difference is due to the current Postgres implementation, which treats all such values as variable-sized, even if all the columns involved are fixed. The value includes type and size information for every component.

Sadly, having explained how to use Composite Types in detail, I now have to tell you that you only want to have composite valued fields in low-volume tables.

Don’t forget all the other ways to employ row-valued functions and such, though!

FIN

This is the end of my first post, about types in Postgres. Based on my experience teachin this stuff to various Postgres using audiences, you probably learned something.